Galleries of

Ivory Carvings

and Scrimshaw

From pre-historic times to the present, ivory has been among the most prized materials known to man. Sometimes it has been brightly-colored, at other times left pure white. It has been used for crude objects to some of the most intricate and ornamented things ever created. This gallery will show ivory from the earliest period of history to the present. It will describe the use of ivory in different geographic areas.

Ivory Portraits and Busts

Ivory Portraits and busts were often commissioned by royalty and the noble class in Europe. Ivory workshops in France, England and Germany many numerous masterpieces, from Emperor Augutus (c. 27 BC-14 AD) to Sir Isaac Newton (1718).

While some portraits were created as miniatures, out of a single tusk, others were life-size, made out of multiple tusks and placed upon pedastals of onyx, wood or marble.

Unlike most ivory carvings, whose carvers remain anonymous, many ivory portraits and busts are signed by their makers. The mojaority of ivory portraits were made from 1600 to 1800.

Ivory portraits and busts are now incredibly valuable and are conserved in the collections of major collections such as the Victoria & Albert Museum and Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ivory Liturgical Combs

Before combs were cheaply manufactures in plastic or metal, they were handcrafted out of various materials. Ivory combs were made by early civilizations, and were hand carved for centuries around the world. Some of the earliest combs date back 5000 years to Persia. In addition to the standard used of the comb (i.e. hair and fiber grooming) combs were also used to make music. The comb is capable of producing humming sounds when used like a harmonica, and thumb piano sounds, when strummed with fingers.

Ancient ivory combs were often double sided. While one side would have smaller, thinner tines and the other side would have larger, stronger ones. The surface are of the ivory would often portray religious scenes, or intricate floral patterns.

Ivory liturgical combs are now extremely valuable artifacts, boasted by collectors of medieval and ancient art.

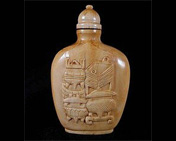

Carved Ivory Snuff Bottles

Ivory Snuff Bottles were widely utilized in China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). At this time smoking tobacco was prohibited, which led to the rise in popularity of snuff, a powdered form of tobacco. By the 18th century, snuff was used among all social classes in China, though the type of snuff bottle remained an indicator of wealth and stature.

Snuff bottles were made out of jade, shell, glass, porcelain, wood, ceramic and ivory. The ivory snuff bottles were often carved or painted with narrative scenes or ornate designs. The ivory snuff bottles are almost always carved out of elephant tusk. The tops of the bottles are attached to a small spoon, used to apply the snuff.

In 16th century Europe, snuff consumers used a similar, box-shaped vessel to store their snuff. These boxes, like the snuff bottles, became status symbols for the borgious to show off to their friends.

Replicas of snuff bottles are still made, and original antique bottles continue to increase in value.

Ivory Mystery Balls / Chinese Puzzle Balls

Intricately carved mystery balls (also called Chinese puzzle balls) have been carved since ancient times. The balls consist of concentrically carved spheres that vary in size and number. Each sphere contains a windowed pattern, revealing the complexity of the inner spheres. While antique ivory mystery balls are among the most precious, other versions have been carved out of jade, soapstone, wood and "Hong Kong Ivory" (a synthetic ivory created out of ground and compressed bone). Antique ivory versions were often accompanied by a carved pedestal, which served to hold and display each mystery ball.

Traditional Chinese mystery balls were carved with a variety of patterns, including dragons, phoenix, flower, peach blossoms and birds. The number of layers usually runs between three and seven, but has reached up to forty-two layers.

The process of making a mystery ball is quite complex and begins with turning a solid ball on a lathe. The ball is then drilled into and reworked with numerous hand-tools. The two strongest, outermost balls are often fused together to prevent the more fragile inner balls from breaking.

Mystery balls continue to be made in modern times, but are mainly made out of synthetic, imitation ivory.

Ivory Crucifixes

Antique ivory crucifixes were carved in various styles and sizes. The crucifix, consisting of a representation of Jesus's body adhered to a cross, is mostly used in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran and Eastern Orthodox churches. In some versions both the cross and corpus are carved from ivory, while in other versions only the corpus is ivory and the cross is wood or metal.

Small-scale ivory crucifixes were easily carved from a single piece of ivory, where larger ivory crucifixes were made from multiple pieces. Smaller crucifixes are used as pendant, rosaries, or to adorn interior furnishings. Larger ivory crucifixes are seen in church altars, and now museum collections. The larger ivory pieces are often partially painted or carry a Latin inscription.

Ivory crucifixes are mostly commonly found in Europe and the Americas, but versions of the ivory crucifix can be found all over the world.

In modern times, crucifixes are made out of wood, metal or synthetic materials, making antique ivory crucifixes particularly valuable.

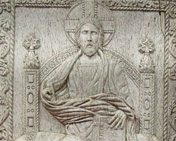

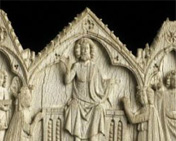

Medieval Ivory

In 726, Eastern Roman Emperor Leo III, enacted a law banning the creation of religious images, known as icons. He ordered the removal of the relief of Christ at the entrance to the imperial palace and its replacement with a cross inscribed "I drive out the enemies and kill the barbarians." Ivory craftsmen left the Eastern Roman Empire and moved west. With the investiture of Charlemagne in 800 as Holy Roman Emperor, ivory carving returned to a place of prominence in Northern Europe. Important ivory workshops arose particularly in England, France, Germany, and Belgium.

Renaissance Ivory

The Renaissance was the first era during which people were so self-conscious that they came up with a name for the era through which they were living. The word "renaissance" means re-birth. To the Renaissance person, human action was responsible for the course of history. It was a time of unparalleled creativity in all the arts and crafts. There was a high degree of skill in the ivories of this period, which were strongly influenced by the Greek and Roman classics.

Chinese Ivory

The earliest ivory found in China dates from the Neolithic period (ca. 5000 B.C.). More ivories have been found from the pre-Ming period (ca.1600 B.C. - A.D. 1368), though they are not as numerous as jade or bone carvings. The majority of the Chinese ivory we have dates from the Ming (1368-1644 A.D.) or Qing (1644-1911 A.D.) dynasties. Beginning in the Sixteenth Century, Portuguese traders and missionaries had contact with the Chinese. The western market had a profound effect on ivory carving. By the late Sixteenth Century, a large percentage of the religious figures in Spain, for instance, were fashioned in China. Ivory worked for the domestic Chinese market were of equally high quality.

Japanese Ivory

Many of the earliest Japanese ivories are deeply indebted to Chinese prototypes. Ivory during the early period was mostly used for inlay and is done in long-established styles. The ancient traditions of Japan were threatened by the arrival of Portuguese, Dutch, and British missionaries and traders in the beginning of the Sixteenth Century. Christianity was banned and foreign influence was driven underground. In the Eighteenth Century, netsuke begin to appear. These Japanese ivory carvings are highly-prized throughout the world. They were used to open and close the small boxes (inro) worn underneath kimonos by both women and men. In the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, the delicately-carved ivory netsuke with charming themes have gained international popularity.

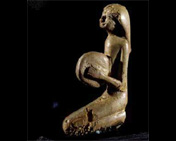

Indian and Near Eastern Ivory

Important ivories have been recovered from the Near East and India from the most ancient archaeological sites. From the Sixteenth Century A.D., ivory was used extensively in India. With the availability of native ivory, and the tradition of highly skilled craftsmen, ivory from the great carving centers in Orissa, Madras, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and the Portuguese colony Goa, were highly-desired luxury items throughout the world.

The motifs of antiquity were retained and refined in the Near East after the advent of Islam in A.D. 622. Chess pieces were the most popular use of ivory in the Near East during the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Centuries. Carved elephant tusks, called oliphants, were carved in Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and other parts of the Islamic world during the Eleventh, Twelfth, and early Thirteenth Centuries. Christian European leaders prized them as symbols of feudal authority. European collectors in more modern times have cherished the meticulous and elaborately-carved ivory from Egypt, Istanbul, and other parts of the Near East.

African Ivory

In most African cultures ivory was an indicator of wealth. High-status Ibo women, for instance, wore massive ivory pieces as a marker of their place in the social and economic hierarchy. Ivory was valued similarly in African and European cultures.

Ivory objects were some of the first worked materials shipped to Europe from Africa when explorers started traveling through Africa in the Fifteenth Century. The "Afro-Portuguese" carvings of luxury items were among the most accomplished ivory carving of the Sixteenth, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century. Nineteenth and Twentieth Century ivory carved for the domestic African market are highly-regarded both for their design and the quality of their craftsmanship.